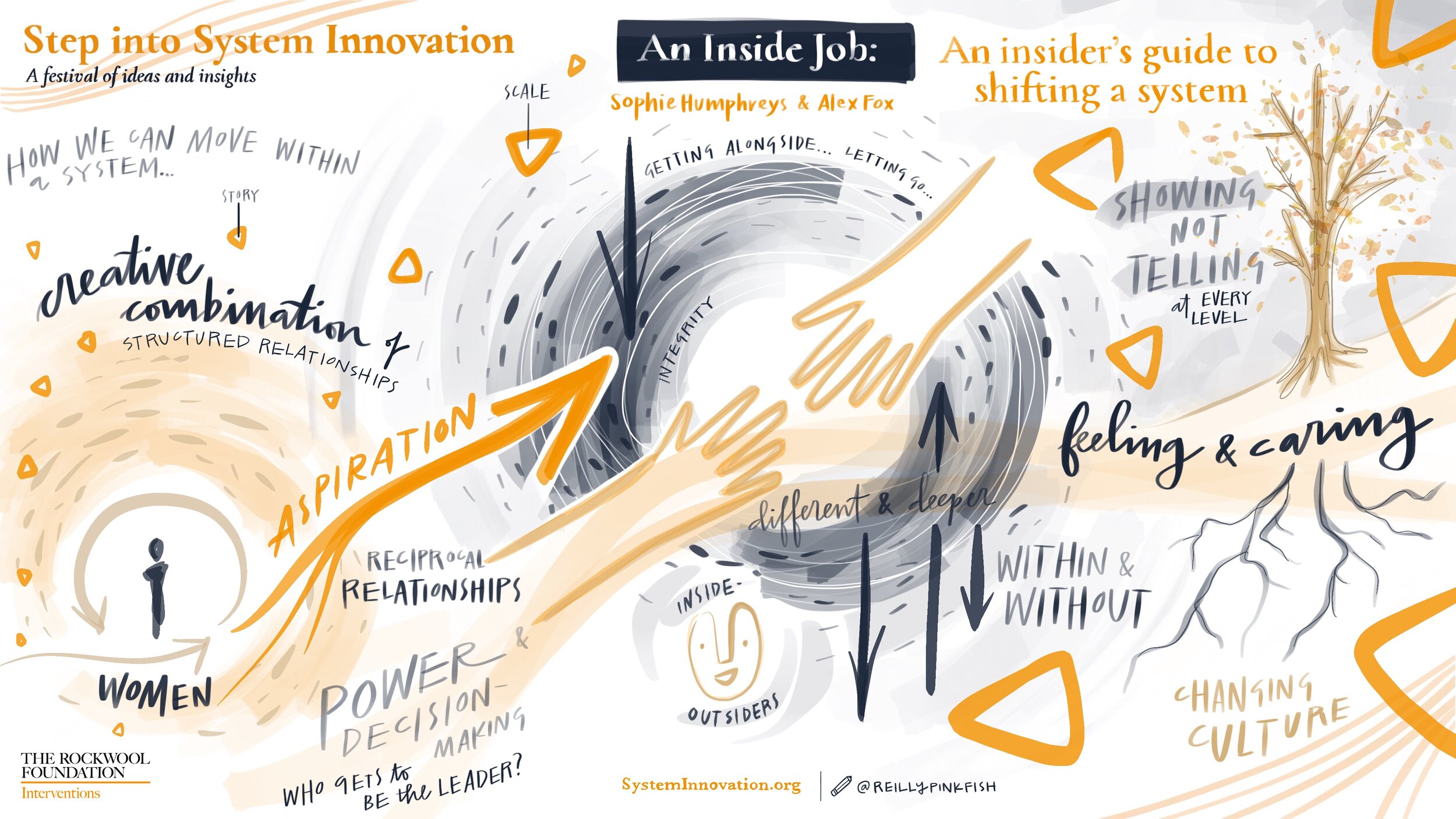

An inside Job: An insider’s guide to shifting a system

This blog post was part of the event Step Into System Innovation - A Festival of Ideas and Insights on Nov 9th to 13th, 2020 and sums up the second webinar of the week. Watch the recorded webinar and read about the event here.

——

Caring is self-realisation brought about through the growth of others. That is how Milton Mayeroff defines care in his classic account On Caring.

Mayeroff’s definition of care came back to me after spending more than an hour in conversation yesterday with Sophie Humphreys and Alex Fox.

Our discussion highlighted a distinction central to our work at the Rockwool Foundation on systems innovation: scaling an innovation is not the same as shifting a system.

An innovation can scale, growing in numbers of users and revenues, without shifting how a system works. Indeed, it’s almost more likely that it will grow without reshaping the system but in fact serving it. Often radical innovations scale only by leaving behind precisely what makes them different. They become creatures of the system they set out to change. That is the price we pay for success.

What Alex and Sophie talked about is how you can both scale and shift a system at the same time, and in particular how projects hang onto their core DNA, the principles and values which make them different and which lie at the heart of what makes them effective.

Let me give you a brief summary of what Pause and Shared Lives schemes do and then touch on the ingredients that Sophie and Alex mentioned in our discussion which are critical to shifting a system, not just scaling your solution. Remember, if you’d like to learn about both initiatives in more detail, you can watch Sophie and Alex’s respective pre-recorded interviews on our festival platform.

The Projects

Sophie is the founder of Pause, a groundbreaking programme working with young mothers who have more than one child who has been taken into local authority care. Pause creates a bespoke programme of support around each woman, with a coach and mentor working alongside her, so she can start to exert more control over her life, shaping a plan for the future. The Pause is created by the woman agreeing to take contraception for a year to prevent her becoming pregnant again, thus breaking the cycle of repeat pregnancy.

The support helps her to start piecing together a sense of how she wants to live free from many of the factors which likely keep her trapped in a cycle of abusive relationships with men and dependence on drugs and alcohol.

Pause, which now works in more than 40 municipalities in the UK, has been extensively evaluated: the most recent of those evaluations, which came out last week, showed that in local authorities where there is a Pause scheme, the number of children being taken into care is going down markedly. In those without a Pause scheme, the number of children being taken into care continues to rise.

Sophie’s explanation is that if you can find the time and space for a skilled practitioner to work alongside a woman in this position, the reciprocal relationship they form can support the woman to break the cycle of abuse and disadvantage which entraps her, at huge cost to her, the children and the state. It’s a structured way to create relationships that change people’s lives at scale.

Alex Fox is chief executive of Shared Lives Plus, the body which represents Shared Lives schemes across the UK. Shared Lives schemes are a structured way for ordinary households to provide care for adults. It started as a way for families to care for adults with learning disabilities and has expanded to work with people with a range of long-term care needs, such as dementia.

Shared Lives stands between the isolation that often afflicts people if they’re left to care for themselves and the impersonality of institutionalised care. Shared Lives’ carers, who are paid, are trained to understand how to care for someone by including them in their household. It does not provide a service but a relationship and it’s that relationship which allows people to live well.

Shared Lives schemes have also been extensively evaluated. The official Care Quality Commission has regularly found that they provide the most cost effective and high quality care. There are more than 10,000 Shared Lives carers in the UK. Local authorities can commission a Shared Lives scheme to develop the capacity of local people to provide for care from within their own homes. It generates local resources for local needs.

Navigating Between Shifting And Scaling

As one of our discussants Vita Maiorano, from The Australian Centre for Social Innovation, put it, both these programmes operate in the hazy middle ground which is often hard to navigate.

They operate within larger systems of public care, social services and health, to name but three. The people they work with are referred to them through these services; the care they provide is regulated and inspected by official bodies.

Yet their approaches embody principles which are quite different to how many of these services operate. They start with the person, rather than a set of needs or conditions to be treated. They both start with that person’s aspirations to live well, rather than focus on their problems and deficits. They put relationships at the heart of living well, rather than providing people with packages of services. They create rather more than they deliver: they do not deliver services to people in need, they enable people to create a better life for themselves. They do that by working with people, alongside them, rather than delivering to and for them.

Sophie and Alex gave a kind of masterclass in how to navigate this messy, middle ground, being inside the system, funded by it, and yet in significant ways at odds with it. How do they manage to have one foot in the system and one foot outside of it?

Put some structure around the relationships they form with their participants. Shared Lives plus trains its carers to know where to draw boundaries: what they can and cannot take on. At the core of Pause’s work are skilled practitioners who know how to be both professional and caring, empathetic and yet independent. As Sophie said: “Social care systems are in a way about protecting people from feeling, because feeling is ‘dangerous’, it’s dangerous to relate. So a bureaucratic system is created to stop those feelings.” Pause is a way to inject the feeling back into care without losing the professional judgement and structure needed for a publicly funded service.

Create some protection for the scheme from the wider system. Alex talked about Shared Lives as a kind of protected space in which carers could form stronger relationships with the people they care for. There is a system for contracting, commissioning, training and inspection, but that does not interfere with the highly relational work Shared Lives carers engage in. It’s an enclave within the dominant system in which an alternative approach to care can grow.

Create good work for the carers. The relationships become potentially transformational because the benefits flow both ways. The carers get more satisfying, rewarding work; the people being cared for get a more intimate, personalised experience.

One of our audience members remarked that hearing Sophie talk reminded her of the philosopher Hannah Arendt’s distinction between work and action. In The Human Condition, Arendt distinguished between labour, work and action.

Labour was the essential, never-ending task for sustaining human life. Work was instrumental, it involved using tools to change the world, leaving a mark on it, for the sake of consumption. Action was how people realised themselves, found their calling and purpose. Too much of what we do, Arendt says, has been reduced to mere labour or work. One way of thinking about what Sophie and Alex are doing is restoring the scope for work to become action, to become meaningful: care is self-realisation through the growth of other people.

It is impossible to scale an approach that is different to the dominant system unless there is a clear account of how rewarding the practical work becomes. It requires creating good work for the carers as a way to create good care.

Understand your DNA and hang onto it. Both Sophie and Alex talked, in different ways, about how their project hangs onto the principles and philosophy which makes it distinctive. As Sophie put it: “ What is your purpose? You have to be sure what is at the core of the mission and stay true to that. Be authentic and maintain your integrity.”

For Sophie, it was essential to maintain the project’s identity even as it adapted, like a chameleon, to different settings. She sells Pause’s benefits in different ways, depending on the audience. There is a core narrative, which sets out the principles behind the programme, but different versions of that arise, depending on whether she is talking to social workers, doctors or local authority commissioners.

Alex said that for the Shared Lives’ philosophy to remain alive, it had to continue to ask difficult questions about who had power in public systems, who was listened to and who could lead.

Scale down as you scale up. Alex talked powerfully about the need to keep hold of a vision of how different public services could be, even as the scheme delivers better value for money within the current set up. As he put it, as you scale up and out you also have to scale down, to ensure you really are sustaining the caring relationships which are the signature of Shared Lives schemes. He calls this the paradox of scale: really effective solutions, which need to be provided at scale, actually involve quite intimate, attentive, bespoke work.

And finally, a few thoughts on how to spread a potentially system shifting innovation, within the system, despite it being quite different from the dominant service logic.

Show not tell. Sophie reminded us that new practices spread not with manuals, not with philosophies, but by showing practical models of how to make a difference. Practitioners in particular learn by emulating and adapting what they see and feel not by being given a manual to follow. Good care involves a lot of tacit knowledge and judgement.

Find the right points of leverage. Rie Perry, the chief executive of Næstved municipality, asked for some advice on how best to inject change into a system. She is responsible for an organisation with thousands of employees. Should she focus on one area in which to start the change and hope it will ripple out? Or should she try to change the culture of the whole organisation, which is an enormous undertaking?

Infiltrate, do not duplicate. Sophie described how the most established Pause schemes are now having a ripple effect through the local systems of child protection and health that they are part of. She attributed that to the infectious principles and practice of the scheme; the fact that people could see it working locally. Vita Maiorano concurred, shifting a system requires a shift in culture, mindset and outlook on the part of the staff and managers involved.

Build alliances based on shared principles. Alex said Shared Lives schemes were scaling while shifting the system because they were building alliances with schemes that follow similar underlying principles. These schemes also build on the assets and capabilities in communities so people can live better lives rather than only focussing on delivering specific services to those deemed to be in need. Alex described a wide array of projects which had a family resemblance to Shared Lives. When these come together, in a locality, then there can be a system-wide shift.

Defeatism is more of a challenge than outright opposition. When Alex was asked how he dealt with opposition to change from within the system, he said that was rarely a problem. Most people like Shared Lives as an idea. There is very little overt opposition to it. The problem is people who like it but cannot see how to make it work. The deeper problem is cultural, rather than about vested interests. The problem is that too many people in public services feel there is simply no way that the larger systems they are part of can shift to a different logic, a different set of operating principles.

Which is why we are keen to develop practical methods, frameworks and tools for people to embark on deliberate systems innovation to create new, better, different social, education, work and care systems for the future.